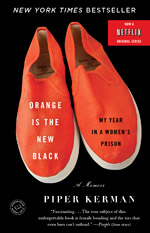

Last night (or more accurately *ahem* early this morning) I finished Orange is the New Black: My Year in a Women’s Prison, the memoir by the now notorious Piper Kerman, a middle class white woman who was incarcerated for smuggling a suitcase of drug money for her girlfriend ten years after the offence took place. Like many people, I was first introduced to Kerman’s story through the Netflix series of the same name, which I absolutely love, so when I saw the book during a trip to my local library (USE YOUR LIBRARIES, PEOPLE) I immediately picked it up. For those of you who are familiar with both the book and the show, you can imagine my surprise. Where the series is a complex ensemble drama about the entangled lives of a group of incarcerated women, Kerman’s memoir is a story of class inequality, a prison system that is ineffectual and unfeeling, and the amazing perseverance and solidarity of the women caught in the middle of it all.

At first, Kerman reminded me rather of Elizabeth Wurtzel. Also a blonde, middle class, American woman, Wurtzel rose to fame in 1994 after publishing her memoir Prozac Nation, chronicling her battle with depression in a way that read to many, including myself, as rather whiny and narcissistic. Now, I actually ended up quite enjoying Prozac Nation (which probably warrants a blog post all of its own), but for most of the book I was deeply annoyed by Wurtzel, and when I first began Orange is the New Black, I was concerned that Kerman was so wrapped up in how dreadful it was that the life of this ‘nice white lady’ had been destroyed (by her own actions, no less) that, as with Wurtzel, this self-pity would overshadow anything else in the novel. I am very glad to say that this is not the case. Although Kerman was, understandably, devastated that she was being sent to prison, what rapidly became apparent is that she is painfully aware of her own privilege compared to many of the women she was incarcerated with. She had a wonderful support network of dedicated friends and family on the outside, a reliable stream of money to buy her own goods (such as toiletries and actually edible food) from the commissary, a job and a home waiting for her when she was released, a fiancé who stood by her and visited every single week, and the money to employ a good lawyer in the first instance, meaning her sentence was significantly shorter than that of many women imprisoned for similar crimes. Also, she was white, educated, and engaged to a nice middle-class man. She is continuously questioned how a woman like her ended up in prison in the first place.

The inequality is what is really at the heart of this book: Kerman is rightfully outraged at the way in which ‘we have built revolving doors between our poorest communities and correctional facilities’, and that prison spectacularly fails at teaching these women the skills they need to break into mainstream society, when criminal and underground markets are all many of them have ever known. Daughters are imprisoned in the same institution to which their mothers were sent before them, often with sisters or cousins in similar facilities. And the revolving door turns.

Another thing that Kerman highlighted is the solidarity, love, and perseverance that the women in these institutions display. They make gifts for each other, celebrate together, comfort one another. They form their own families, their own support groups, and far from being a danger, Kerman portrays her fellow inmates as a constant source of love and sisterhood. It’s a far cry from the accepted narrative that your fellow prisoners will be the largest danger you will face in prison: the danger to these women comes from incompetent or bullying correctional officers (or COs), and from being caught in cycles of poverty, addiction, and poor education that prison does very little to rectify.

But where is Alex, I hear you cry! Where are the lesbians? Well, reader, I spent the whole book saying the same thing. I waited with baited breath for the moment when Nora, Alex’s real life counterpart, would come strutting into Danbury and sweep Piper off her feet. But, alas, it was not to be. Nora does make another appearance, but there is no affair, and there is certainly no sweeping. If you want gay ladies, I would stick with Sarah Waters. The lesbianism in this novel is there: Kerman is frank about the nature of her relationship with Nora, and there are several openly lesbian woman in the the prison, but there is no sex, and it is all handled in a very matter of fact manner, with no sensationalism or gratuitous sapphic dabbling. I was only a little disappointed. All in all, I found this an interesting and enjoyable read, more in the line of Girl, Interrupted than Cell Block H. If you want an educated exploration of the pitfalls of the US prison system and the women trying to overcome it, then definitely give it a go. Kerman’s narrative is amusing, warm, and nowhere near as irritating and self-involved as Piper Chapman can be. However, if you were looking for a Piper x Alex fix to fill the void after the end of OITNB season 3, you may just have to sit tight and wait for season 4.

Image via Piper Kerman

Recent Comments