Publisher: Random House

Year: 2012

ISBN: 978-0-09-956183-5

No. of Pages: 224

‘”I have sold my soul,” she said. “I have signed in blood.”’

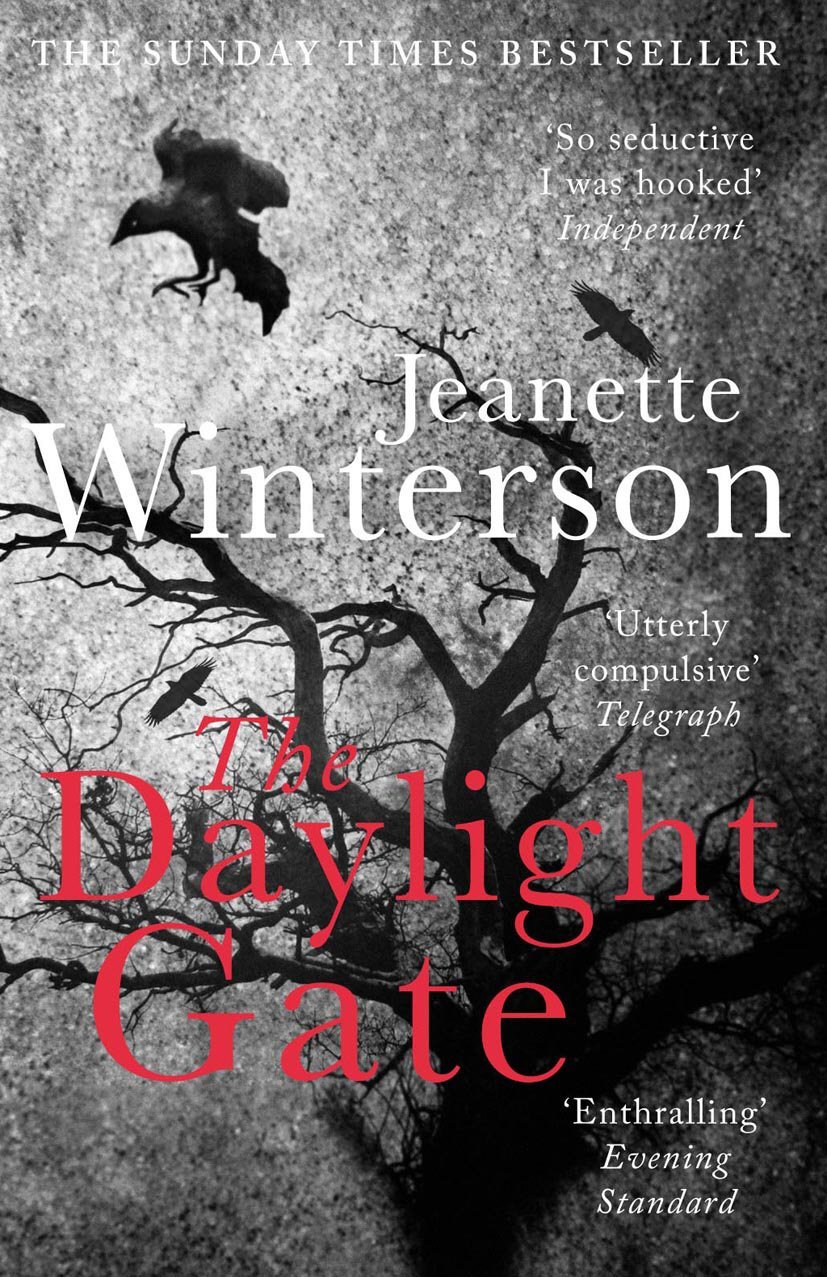

As a literature loving Pagan lesbian (try saying that when you’re pissed), you can imagine how excited I was to stumble across The Daylight Gate. This novella is the latest offering from Jeanette Winterson and is a fictional account of the days leading up to the infamous Pendle Witch Trials, published in 2012 to commemorate the 400 year anniversary of the executions. Many, myself included, know the story of the little girl who testified against her own family and her neighbours, sending them all to the gallows for witchcraft, but Winterson’s take is a chilling retelling of political agendas, personal vendettas, and demonic pacts where it’s not just your life at stake, but your soul.

Jeanette Winterson, OBE, was born in Manchester but raised in Lancashire, where The Daylight Gate is based. She rose to fame with her first book, Oranges Are Not the Only Fruit, in 1985, and has continued to enthral readers with her subsequent novels exploring themes of physicality, sexuality, and gender identity. Despite the prevalence of queer themes in her work, Winterson is not confined to the category of “lesbian writer” and has achieved popular recognition, winning several prizes including the Whitbread Prize for a first novel, the E. M. Forster award, and two Lambda Literary Awards, as well as her OBE for services to literature.

Winterson’s historical fiction is always interesting. As in her 1987 novel The Passion, Winterson is free and easy with historical accuracy in this novella, using the history as a setting, a background against which her characters stand. Winterson herself said that ‘The Passion isn’t an historical novel. It uses history as an invented space. The Passion is set in a world where the miraculous and the everyday collide’, and in many ways The Daylight Gate is the same. The characters are real historical figures, but Winterson has made them her own. She takes the accusations of devil worship and witchcraft levied at these women and uses it as fact, introducing a level of supernatural horror in addition to the gruesome physical abuse these women are seen to endure: rape, torture, and state sanctioned murder. However, the way that Winterson does this makes for an interesting and in many ways disappointing power dynamic in this novel. Contrary to witchcraft providing women with power and agency of their own, it is shown over the course of the story to be something that is bestowed on women by men (or male appearing characters. Whether or not they can be men if not human is up for debate). It’s hard to say much on the subject without huge plot spoilers, but the portrayal of women as the agents of male power was somewhat disappointing, especially considering the increasingly feminist (if occasionally trashy) portrayal of witches in recent years. However, I did love the division between the ceremonial magic and alchemy practised by Dr Dee and the folk magic of the Device family, and it isn’t at all true to say that the women of this novel aren’t powerful. However, it is Alice Nutter’s money that allows her her agency, not her knowledge of alchemy. And, of course, her fierce intelligence.

But really these criticisms are mere pet peeves: considering the setting, it’s amazing these women have any power at all. When it comes to how enjoyable the novel is to read, Winterson is brilliant as ever. Although I confess to being slightly disappointed with the very end of Christopher Southworth’s story, Alice Nutter’s was wonderful, and I ripped through this novella, finding it just as gripping as Winterson’s previous work. As always, Winterson’s prose was absolutely gorgeous: the short, blunt sentences highlighting the brutality of what is being described, and the storyline that emerges about Alice Nutter and the beautiful Elizabeth Southern was brilliantly handled. Winterson always handles queer sexuality without being heavy handed, and presents human relationships as fluid and natural. Her queer characters never feel tokenistic or gimmicky. She brilliantly captures the political climate of 1612 Lancashire: the paranoia and fear of the establishment, as well as a politician’s self-serving desire to get ahead, is encapsulated in Potts and his determination to both capture Southworth and expose the Pendle women as witches, whatever the cost. The Daylight Gate is a hugely enjoyable book, at times genuinely chilling, and a definite read for any one who, just as dusk is falling, feels they could believe in magic.

Leave a comment