“Everything comes full circle, and when it happens I want you to imagine me there to greet you.”

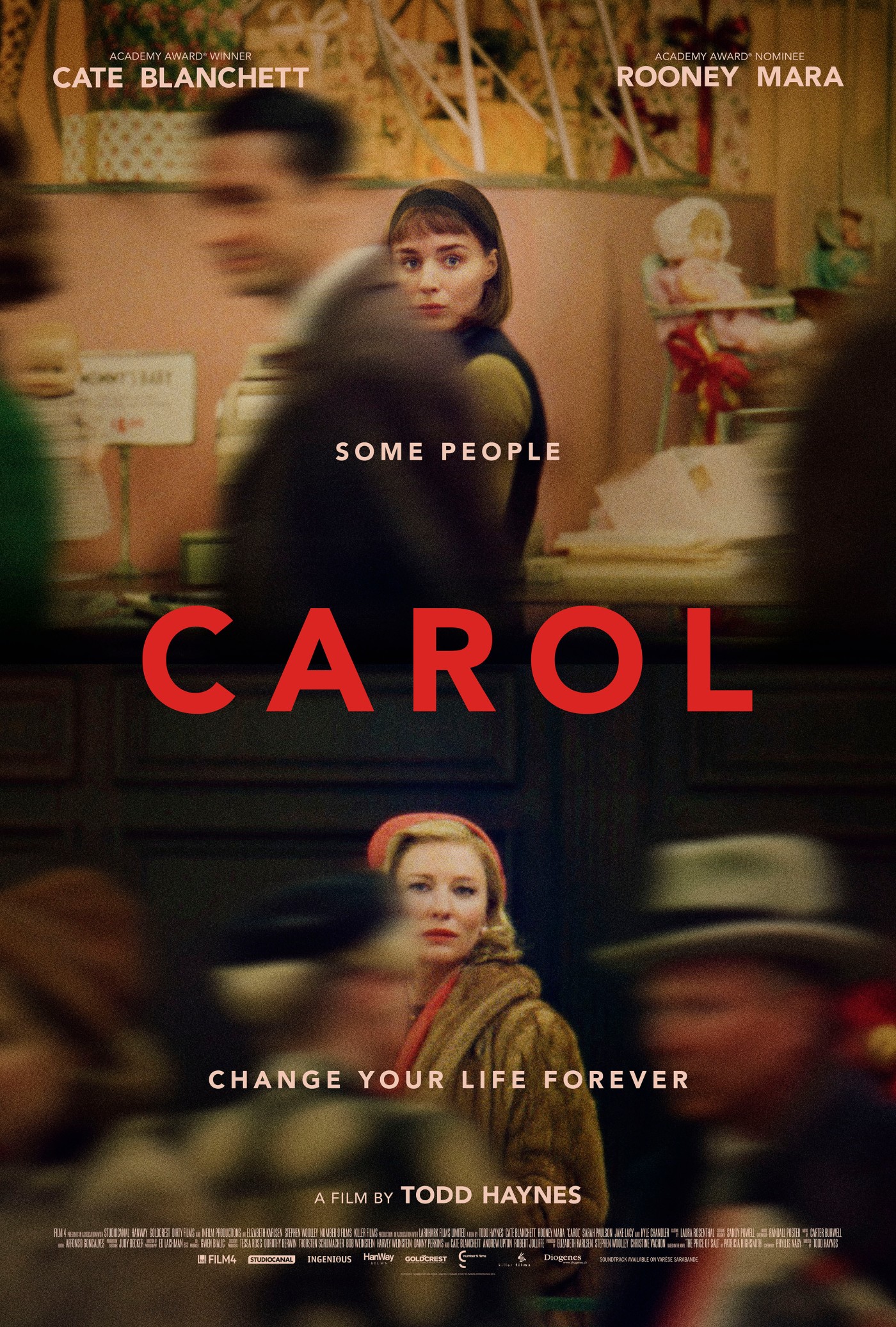

Before I say anything, before I even open my big fat mouth, look at this. LOOK AT IT.

Is that or is that not the most beautiful thing you have ever seen? Those costumes. Those colours. Cate Blanchett. A period drama with lesbians. I must have been super good this year, because Carol is gonna be one hell of a Christmas present. Forget James bloomin’ Bond, this is the highlight of cinema for 2015. Not even Suffragette got me this excited.

But Grace! You say. This is a book blog! Why do we care about some crappy movie? Because, reader, this film is an adaptation of one of my favourite books of all time. And unlike when they filmed Inkheart (WHY, BRENDAN FRASER, WHY!?) this adaptation looks like it’s going to be a good one. It’s already had some killer reviews (including this awesome one from Autostraddle, the leading authority on all things lesbian), and the teaser trailer is so beautiful I have watched it about 15 times and it still makes me well up.

I just watched it again. I don’t think I can wait another 5 weeks, my head may explode.

Based on Patricia Highsmith’s novel of the same name, Carol is the story of Therese, a young woman working in a department store over Christmas, who meets an older woman, Carol, buying a gift for her daughter. The two strike up an affair, but Carol’s rapidly deteriorating marriage becomes an obstacle. It’s hard to say anything else without major plot spoilers, but Highsmith’s talent for keeping the reader uncomfortable really comes into play, here. The book has the feel of the thrillers Highsmith is best known for, constantly driving you forwards, while showing you a romance between two women who found each other against all odds. Published under the pseudonym Claire Morgan in 1952, The Price of Salt, as Carol was originally called, sold over a million copies but, despite sales, Highsmith didn’t reveal her association with the novel until late in life because of its homosexual content. When I read it a few weeks ago, I absolutely adored it. The imagery is beautiful, and it is so wonderfully tense it keeps you on the edge of your seat right up until the last page. The ending is an interesting one considering the time that the novel was written, and homosexuality is treated without any suggestion of perversion or negativity, unlike many of the 1950s lesbian pulp novels which were its contemporaries, the problems they face coming from larger society rather than from within the women themselves. Highsmith is such a talented writer, it was always going to be awesome, and with a cast and crew this good I can’t imagine the film could go far wrong. BUT, only time will tell! Go, read the book. Mentally and emotionally prepare yourselves. I am off to watch the trailer on repeat and weep over the beauty of Cate Blanchett’s hair.

Carol is released in UK cinemas on the 27th of November 2015.

In other news, no post for the next couple of weeks as I am off graduating (screams into the abyss). I will return soon with more ramblings about books / book related doings / things that I’m excited about.

Image via Empire Online

Recent Comments